This weekend, Paul Batters of Silver Screen Classics is hosting his first blogathon, The 2020 Classic Literature On Film Blogathon! I signed up when I heard about this blogathon, planning to participate with a 100 New Code Films article. I decided not to watch and review the film I had in mind after all, but I still want to participate in this fascinating blogathon. Thus, I am joining with a Code Concepts article instead.

I started this series during #CleanMovieMonth85 last July, when I replaced my usual Breening Thursday articles with weekly Code Concepts articles. In these articles, I explain general principles, guidelines, and standards from the Breen Era rather than discussing them as I come upon them in individual films. I have yet to publish articles in this series with any regularity, but this seems like a good opportunity to add the fifth entry.

Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier in Wuthering Heights (1939), a story about which the PCA had some reservations.

When he announced his blogathon, Mr. Batters pointed out that films have used classic literature as source material since the beginning of the industry. It is always a challenge for a movie to present a great piece of literature entertainingly on the screen while remaining somewhat faithful to the original story. During the twenty years of the Breen Era (1934-1954), filmmakers had an additional challenge. They also had to be sure that the stories followed the Motion Picture Production Code’s standards for decency, or their movies couldn’t be distributed in America. Thus, the Production Code Administration was an important part of the creative process throughout every stage of production for all American films during those years.

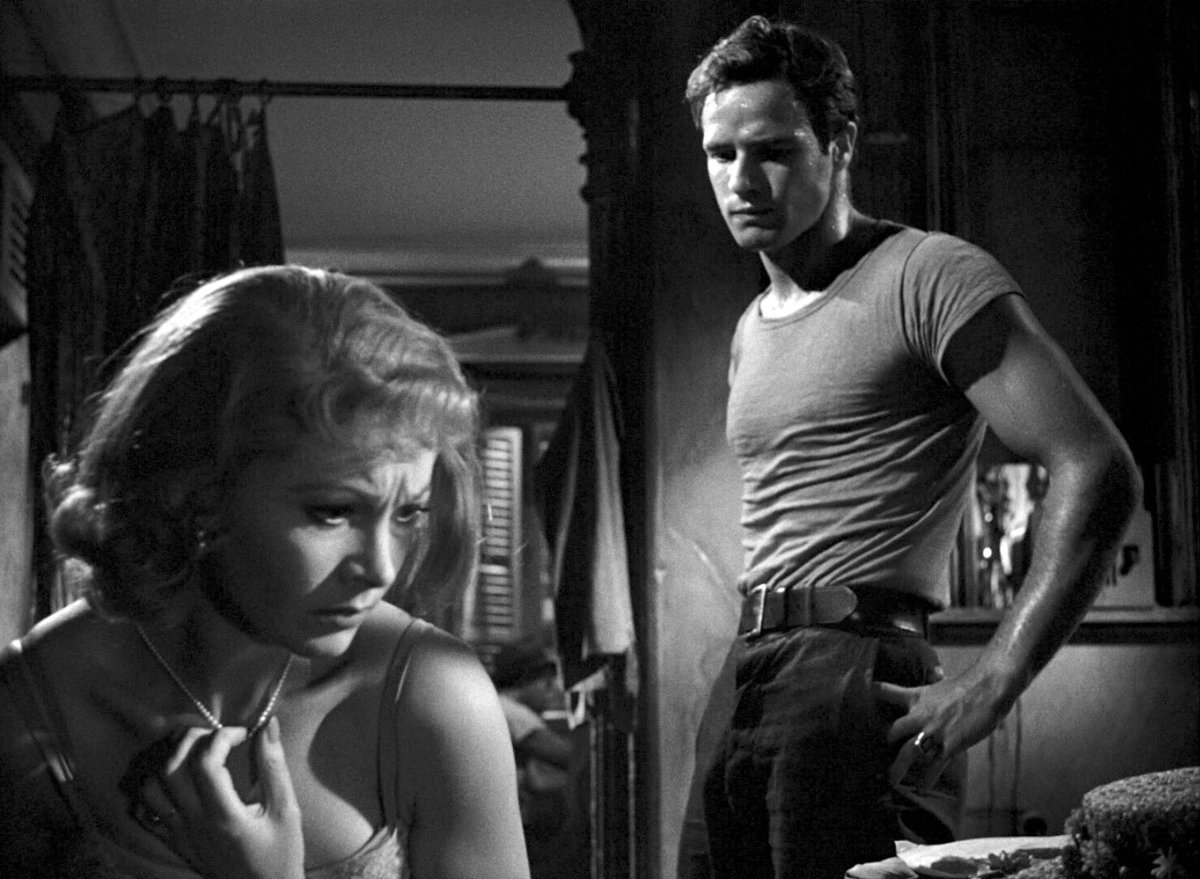

Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), which came from a controversial play which needed significant revision to be a Code film.

Before production began on any film from some outside source, such as a novel or a play, the source material was sent to the PCA for approval. No producer, director, or studio wanted to pay thousands for a story which could never be made into a Code-compliant film. The PCA then sent a reply mentioning the revisions, deletions, and changes which would be necessary for filming. They rarely forbade a story to be made into a movie, although they would send a discouraging letter if the original story contained many violations. An amazingly large number of successful films were originally discouraged from production by the PCA. Even those sources which were considered basically acceptable contained a few points which required warning about revisions.

Although Joseph Breen of the PCA said that a film adaption of this controversial novel would bring down the industry as a whole, it was made into a successful film.

The PCA did not usually tell a filmmaker that he must not proceed with a certain film project, but he was forewarned that certain changes would have to be made. He could make any story he wanted to, if he was willing to cut out or alter the objectionable parts. In some cases, little more than the title and the central idea remained, and sometimes even the title was changed to remove any lurid reputation the source material might bear. Altering stories significantly from their original sources was not a problem for old Hollywood, which made drastic changes without any prompting from the self-regulators.

Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer in Romeo and Juliet, an MGM adaption of the Shakespeare play which some considered too theatrical.

Shakespeare was not a favorite of the PCA, since his iconic plays were famous for their confused romantic situations and none-too-subtle innuendos. However, they were also considered difficult to make from a film standpoint, so the self-regulators didn’t have to contend with editing the writing of the sacred Bard of Avon too often. Notable adaptions of Shakespeare works from the Code Era include A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), Romeo and Juliet (1936), Tower of London (1939), Macbeth (1948), and Julius Caesar (1950 and 1953). Although Hamlet (1948) won numerous Academy Awards, it doesn’t count, since it was a British production and thus not a Code film.

Jose Ferrer and Mala Powers in the 1950 film version of Cyrano de Bergerac.

During the Golden Era of Hollywood, the main purpose of any film (aside from making money, of course) was to be entertaining. It was more important for a film to be an effective piece of cinematographic entertainment than a faithful adaption of any play or novel. However, many Code films from classic literature are regarded as excellent if not the best adaptions of their source material, in spite of artistic license and PCA-suggested revisions for Code compliance.

Let’s consider the Code versions of some famous pieces of literature. I will mention changes which were made for Code compliance rather than for film artistry.

Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier in Pride and Prejudice (1940)

Pride and Prejudice (1940)

This wholesome Jane Austen novel required few changes to be a Code film. The 1940 film, which starred Greer Garson, Laurence Olivier, Maureen O’Sullivan, Bruce Lester, and Mary Boland, did not include every incident in the book for screen brevity, but director Robert Z. Leonard succeeded in capturing the witty humor and refined charm of the original story. The only change which was made for Code compliance regarded the character of Mr. Collins (Melville Cooper), the Bennets’ cousin who will inherit their estate. In the novel, he is a clergyman. However, due to the Code’s rule that members of the clergy be neither comical nor evil, this humorous character is a librarian in the film.

Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

This dramatic film, which starred Charles Laughton as the deformed bell-ringer and Maureen O’Hara as the gypsy girl, Esmeralda, in her film debut, is considered one of the best adaptions of Victor Hugo’s immortal French novel, Notre-Dame de Paris. In addition to the necessary restraints of violence and brutality, this film also required the change of a clergyman to some other profession. This man of the cloth was a villain rather than a comical person, which was likewise forbidden. The person in question is Claude Frollo, the villainous 36-year-old archdeacon of Notre Dame. In the film, Claude Frollo, the archdeacon, is an older man and a totally good character played by Walter Hampden. Instead, the villain is his younger brother, Jean (or Jehan) Frollo (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), who was changed from the drunken juvenile delinquent of the novel into the middle-aged chief justice of Paris. It must be noted that this change was also made in the 1923 silent film starring Lon Chaney, which was made before the Code was written. However, the change would have been mandatory in the Code film anyway.

Fredric March and Charles Laughton in Les Miserables (1935)

Les Miserables (1935)

Although it is most famous as a Broadway musical affectionately called “Les Mis,” Victor Hugo’s French novel about the French revolution has been made into non-musical adaptions, including the 1935 film starring Fredric March and Charles Laughton. Anyone who has so much as listened to the soundtrack of the musical knows that this dramatic story contains several Code violations. The largest of these is the fact that Fantine becomes a woman of the oldest profession to support herself. This element, as well as her selling of her hair, is not included in this film version. The only slight reference is the fact that, at one point, Fantine (Florence Eldridge), is supposedly dressed like a woman of the streets. Also, Marius (March) and the other revolutionaries are attempting only to reform the conditions in the French galleys rather than to overthrow the government, as in the novel. Marius even states that they are not revolutionaries, which keeps the film from glorifying rebels.

Claude Rains and Susanna Foster in Phantom of the Opera (1943).

These are just a few examples of the literary sources which, with some revisions, became excellent Code films. When these stories have been made in other time periods, these changes have not been necessary. However, their inclusion has often led to harsher ratings and inappropriate material which keeps younger audiences from seeing them. These Code films could be viewed by everyone, which meant that people of all ages, classes, and creeds were exposed to these timeless stories. Films are a great way for classic literature to be enjoyed and reach new audiences!

From double beds to sleeping pills, every Code rule had a reason.

Follow us to bring back the Code and save the arts in America!

We are lifting our voices in classical song to help the sun rise on a new day of pure entertainment!

I love classic literature and I really enjoy seeing films based on them! I really want to see the 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice. Knowing that they are in Code years can take some stress off my mind of if there are tricky elements in there. I recently read Anna Karenina which was amazing and I am looking for film versions. And while I do want to see the 2012 version, I’m a little worried about the content. I just learned of versions in 1935 and 1948 which I now am looking forward to seeing also because they are in Code years!

MovieCritic | Movies Meet Their Match

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for leaving this comment! I like films made out of classic literature, as well. I know that you will enjoy the 1940 “Pride and Prejudice.” It doesn’t contain everything from the book, but it is a really enjoyable movie. I haven’t seen the classic “Anna Karenina” films either, but I would love to! I am curious to see them, as well, especially the 1935 with Greta Garbo and Freddie Bartholomew, since that is a Code film. The 1948 version is a British film, so it wasn’t self-regulated. Anyway, there are a lot of great Code literature films. Thank you for reading!

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLike

Even though I’ve only read two articles, I really enjoy this series! I always feel like I learn something new about the Code. By the way, I nominated you for the Sunshine Blogger Award! Here’s the link to my award post:

https://18cinemalane.wordpress.com/2020/04/10/i-won-sunshine-blogger-award-number-four/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Sally,

Thank you so much! I really appreciate that. I’m glad that you like these articles. Thank you so much for nominating me for the Sunshine Blogger Award! I am honored. I will write my reply article soon.

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! I can’t wait to read your award post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent reminder of how the Code brought about some of the greatest movies the world will ever know. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! I appreciate your comment. I’m so glad that you believe in the power of the Code, as well.

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLike

What a fascinating and informative article about the influence of the Code on literature adaptations. I feel smarter now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Brittaney,

Thank you so much! That’s very kind of you. I’m glad that I shared some interesting information with you. I appreciate your comment.

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLike

I enjoyed your very interesting article very much. I will look at other adaptions in the era through this lens.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Patricia,

Thank you so much! I’m glad that you enjoyed this article. I’m so happy that I have given you a different perspective for Code films. I appreciate your reading and commenting!

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLike

Pingback: The 2020 Classic Literature On Film Blogathon Is Here – Day Three – Silver Screen Classics